The Soul Behind the Music

What happens when a musician seeks asylum in another country? What part does music play in that journey? Josephine Burton talks of her friendship with Marouf Majidi, and explores how music transformed his experience of belonging.

I met Marouf Majidi in 2017 at a café in Helsinki. It was a brief encounter. On the previous day, I’d asked some music friends in Finland whom I should try to meet. Marouf was top of their list. But my time in the city was so short- Marouf kindly met me on my way to the airport.

Over coffee, Marouf explained that he was Kurdish, originally from Iran and had had to flee overnight for political and musical reasons to Turkey. He’d eventually been relocated by the UNHCR to Finland, around fifteen years before. I asked him how it had been for him to make music in Finland. He reflected that for years he felt out of tune with the musicians he played with. He was always the soloist, separate from the ensemble, and never gelled. He explained that eventually this shifted and he found his musical place and home in Europe. But when he was able to travel and return to Central Asia and even Iran, he no longer felt fully in tune there.

…for years he felt out of tune with the musicians he played with.

I remember asking him at the time if this tuning challenge was because of the different musical scales. Marouf trained in Persian Classical maqam music in Tehran and plays the tar and also the Kurdish Tanbur. Maqam is played on an entirely different modular musical system involving amazing micro-tones which I still all these years later, struggle to be able to sing with him. Marouf acknowledged that this was part of it but there was also something psychological for him in that sense of dissonance.

Our conversation stayed with me long after I’d returned to London. At Dash we were just embarking on a programme of work exploring what it means to be European. Here was Marouf who had become European, through a difficult and challenging process, and had found a sound in Europe that was different to the sound from where he’d originated. I was keen to learn more from him and about his journey and if possible, work with him. And also to understand if his experience was familiar to others who had also sought a new life in Europe. Perhaps it’s those who move to Europe who can help us understand who we are?

Perhaps it’s those who move to Europe who can help us understand who we are?

Marouf Majidi on stage at WOMEX in Tampere, October 2019

Paban Das Baul, Baul singer originally from West Bengal, India, and his wife Mimlu Sen in their caravan at Ariane Mnouskine’s Cartoucherie in Paris.

Thanks to a grant I received from the British Council and Arts Council England, I was able to travel a little in 2018 across Europe to meet and speak with other artists. The conversations I was privileged to be part of were amazing and eye-opening. I met many Syrian musicians who had fled across the Mediterranean. I heard them play on precious instruments that they had carried with them on boats or borrowed replacements. Fascinatingly many of them found that their repertoire had totally shifted since arriving in Europe. Despite having played rock, jazz or even classical music before, now they were playing as part of more traditional Arabic ensembles. Several explained to me that it was good to have an expertise, to be able to play something that was theirs. One violinist who had once played in the Iraqi National Symphony Orchestra and had toured to Kennedy Center as part of a soft power exercise in 2003, had not been able to find work in the orchestras in Brussels, perhaps he thought because his training in Baghdad didn’t match Western European Conservatoires. Only now in Europe, for the first time, he’d found himself playing Classical Arabic music.

I met highly talented musicians from Sierra Leone, Senegal, Nigeria, Mali and Congo. Quite a few of the older guard had found label and agent support in Europe, but most of the younger musicians were struggling to build their careers there. They had sought safety and security in Europe but returned to the continent of Africa to play and make money.

Quite a few of the older guard had found label and agent support in Europe, but most of the younger musicians were struggling to build their careers

Wherever I went, I asked people about this sense of tuning – whether they’d found a sense of dissonance when they first arrived. Clearly everyone’s experience was unique - and I met people in 2018 who were recently arrived from Syria and others who’d first made their homes in Europe up to 30 years previously. But many identified with Marouf’s experience and shared similar stories with me. Most of those able to reflect, particularly those who were settled and had leave to remain, reported that they longer felt out of tune in their practice and in their lives.

Most of those able to reflect, particularly those who were settled and had leave to remain, reported that they longer felt out of tune in their practice and in their lives.

I began to wonder if the dissonance was in some way related to trauma – that their relocation and all the individual upheaval, disruption and danger that each had undergone, impacted on their ability to hear themselves as they were used to. In the course of the research, I spoke to psychiatrists and neuro-scientists, and learnt a great deal about the amygdala, stress, hearing and balance. There’s an enormous amount of research out there around these issues and I fundamentally can’t claim to be an expert.

BUT I definitely came to a real understanding in conversation with so many extraordinary artists, who’ve sought and built sanctuary in Europe, that their journey and transition into a new environment affected their ability to hear and to play. That this lack of balance in their lives created a dissonance in their music. And that somehow as they sought musical colleagues and played, and slowly established themselves in a new place, the balance and tuning returned. And in Marouf’s case, actually shifted in some way. I love the idea that music was so wrapped up as part of the healing process for so many of the people I met.

I love the idea that music was so wrapped up as part of the healing process for so many of the people I met.

Doudoumah Magou originally from Senegal and Raphaelle Murer at the home of Villes des Musiques du Monde in Paris.

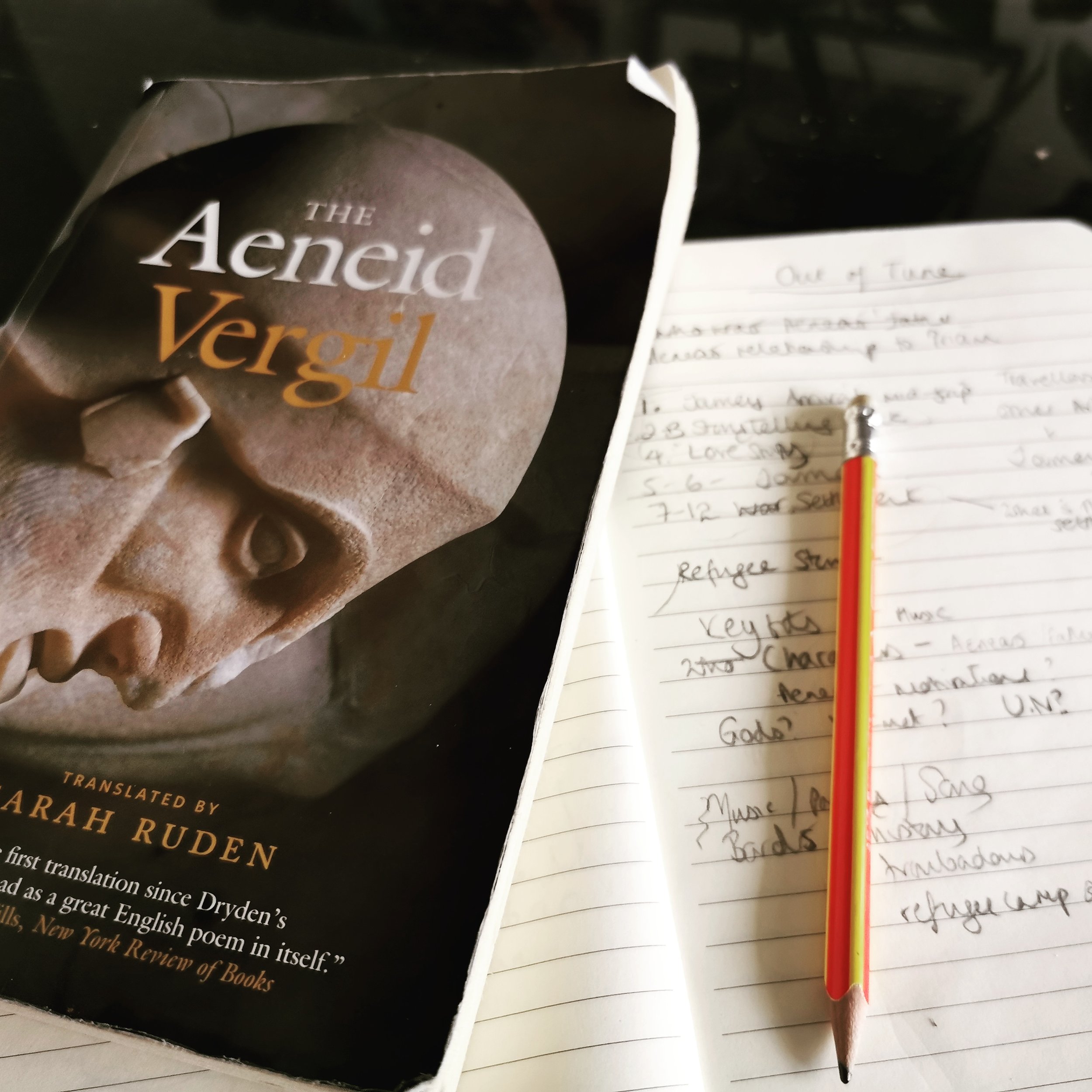

Josephine’s notes on The Aeneid during her trip to Helsinki, 2019.

The conversations and their stories informed Marouf and I, and later the playwright Hattie Naylor, as we developed our show, Dido’s Bar. It’s a show grounded in an old myth, the story of a refugee Aeneas fleeing the destroyed city of Troy to found a new city elsewhere, but is inspired by Marouf’s own personal story of flight and many others like him.

We’re just in the early ripples of the production tide that will carry us into our show this Autumn – casting, designing and completing the score and script. Hattie has managed to sneak in a reference to Marouf’s ‘out of tune’ experience into the final version of our script which I was delighted to read. It’s an acknowledgement of the amount of research and gratitude to the many brilliant people who shared their stories with me and us all, along the way.

There are so many people to thank – but some special gratitude to Els Rochette, Globe Aroma, Yuriy Gurzhy, Daniel Brown, Malick Pathé Sow, Mayssa Issa, Mourchid Baco and Samira Brahmia.

- Josephine

Refugee Week 2022 takes place 20-26 June. This year’s theme, Healing, has inspired us to explore the healing power of music for those seeking sanctuary, in conjunction with our developments of Dido’s Bar. Find out more about Refugee Week here.